From theoretical physics to data science, machine learning, and climate action — I thrive on tackling complex, meaningful challenges.

About Me

Welcome! I’m a physicist specializing in simulations, data science, and AI, with a PhD from Frankfurt on transport phenomena in heavy-ion collisions. My path—from international research to open science and climate advocacy—merges deep analytical thinking with a drive for real-world impact. Here, I share projects, publications, and ideas at the intersection of physics, machine learning, and responsible innovation.

My Projects

Explore my work and insights

Discover a selection of my research and software projects. They cover a wide range of topics, from high performance computing for physics simulations to data analysis and chatbot tuning.

ZüNIS

Leveraging normalizing flows for faster integration of particle collision cross sections.

Bayesian Inference

State-of-the-art statistical analysis of vast datasets for model tuning. This project was one of the core achievements of my dissertation.

Causal Tracing

I analyzed how models like GPT process, store and retrieve factual knowledge by studying the effect of noise and reconstruction of weights.

Get in Touch!

If you’re looking for collaboration or have questions, I’d love to hear from you. Let’s connect and explore what we can achieve together.

By sending this form, you agree to my Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

Bayesian Inference

In this project, I used Bayesian analysis to compare simulations of nuclear collisions — where matter reaches extreme temperatures and densities — with experimental data from heavy-ion experiments. These collisions create conditions similar to those of the early universe, offering insights into how matter behaved microseconds after the Big Bang.

To extract those insights, I built a full inference pipeline that linked large-scale simulations with modern statistical tools. We ran thousands of simulations with varied input parameters, trained surrogate models using Gaussian processes, and applied Bayesian inference to estimate the most likely physical conditions behind the observed data.

This project lies at the intersection of theoretical physics and data analysis. It required handling uncertainty, navigating high-dimensional parameter spaces, and developing tools to connect models with reality. The techniques I used—such as statistical learning, dimensionality reduction, and surrogate modeling—are widely applicable to complex data challenges in and beyond science.

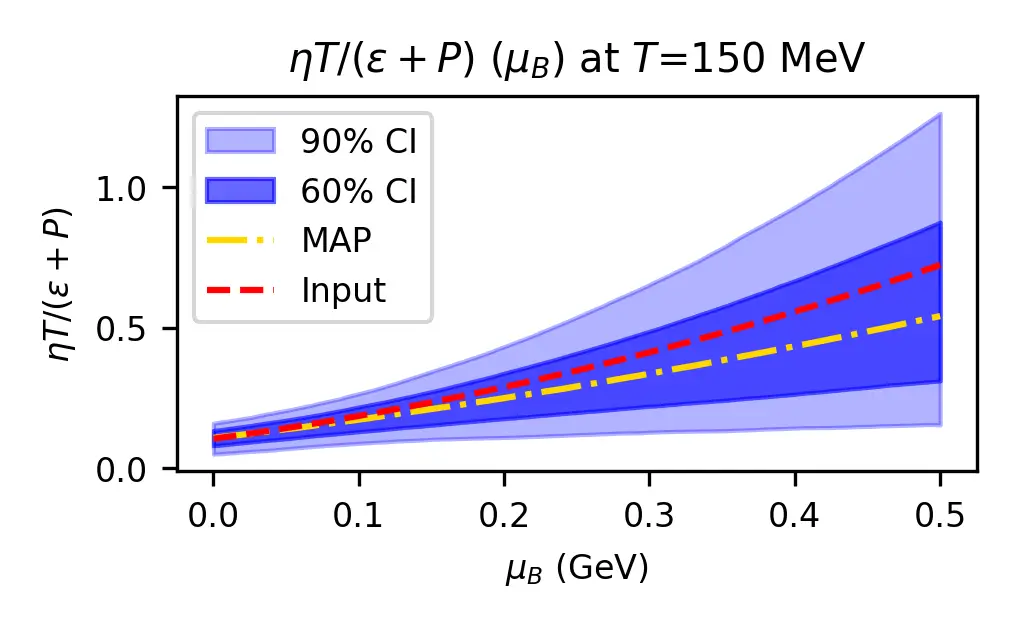

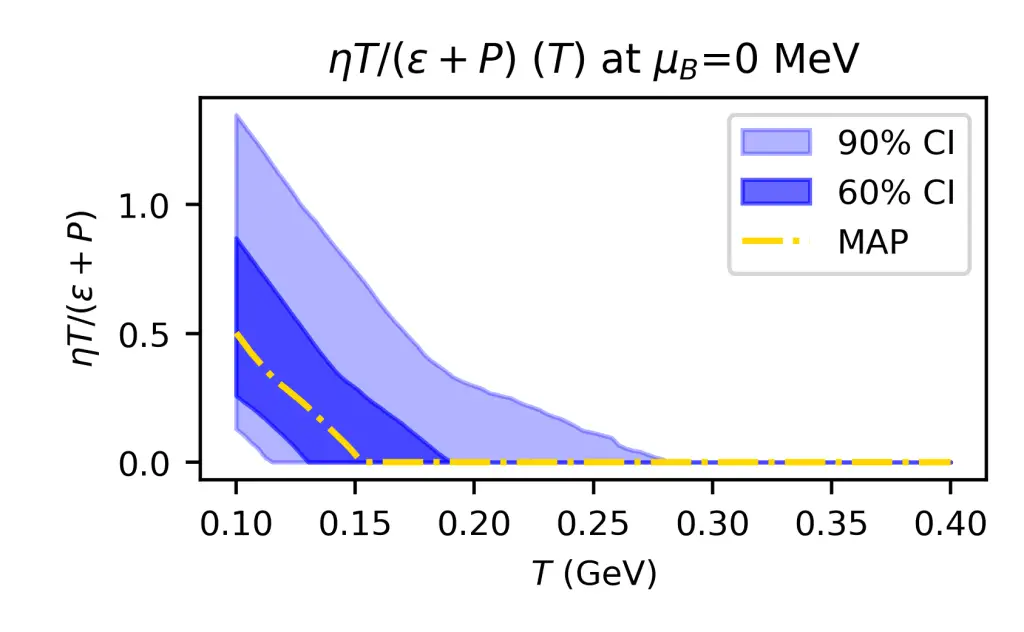

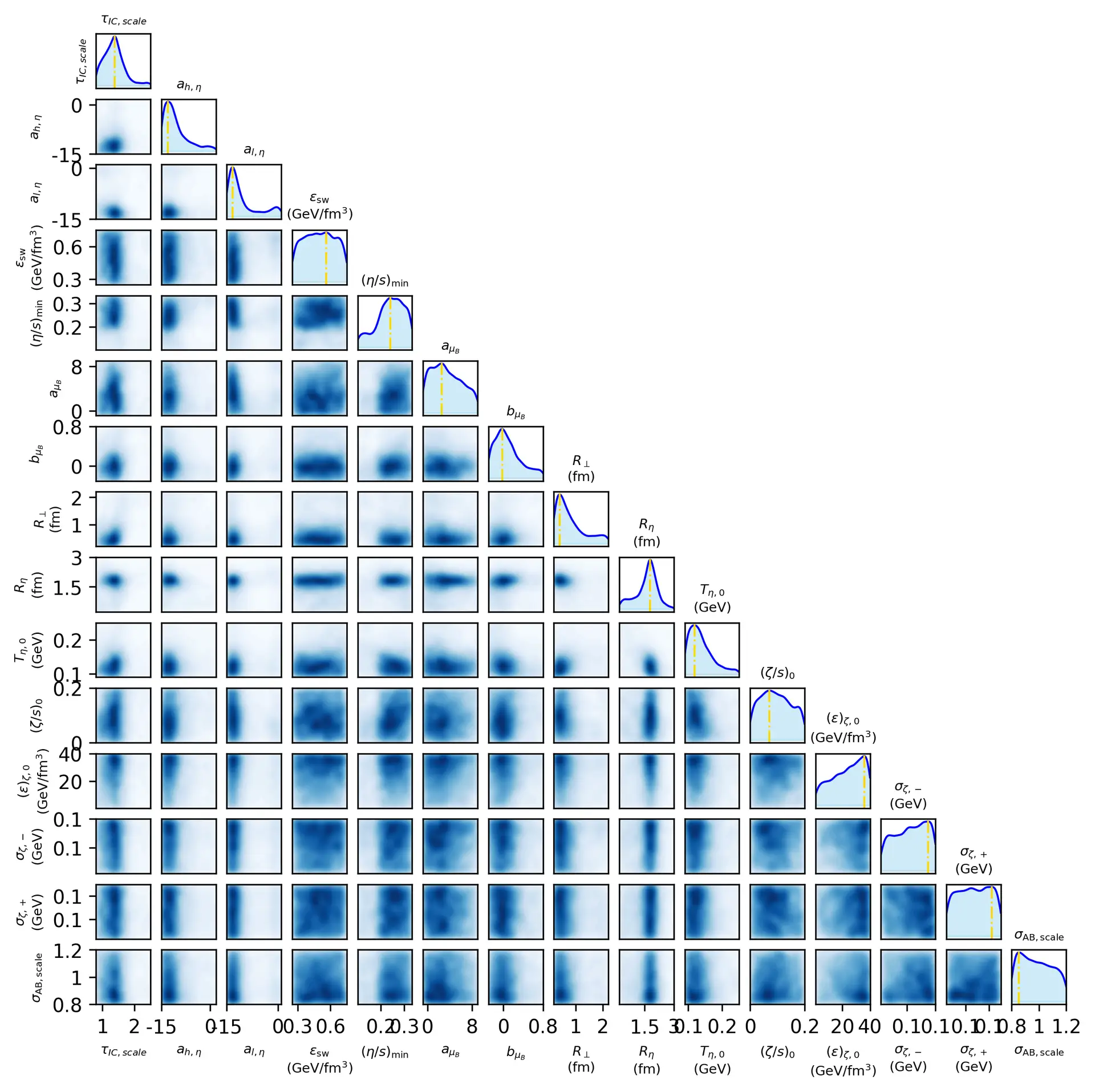

In the pictures, you can see on the top hand the result of our prediction of the viscosity of nuclear matter, as a function of the temperature. Our model predicts rapidly decreasing viscosity, in contrast to most other models on the market. This reveals substantial residual theory uncertainty. On the bottom, one can see the full posterior of all model parameters, allowing one to study correlations in the posterior.

Knowledge in LLMs

Large language models like ChatGPT appear to “know” all sorts of facts—from who the current president of France is to obscure trivia. But under the hood, these models are made up of hundreds of hidden layers of numbers and calculations. One of the big questions in AI safety and transparency is: Where exactly is that knowledge stored, and how does it move through the model?

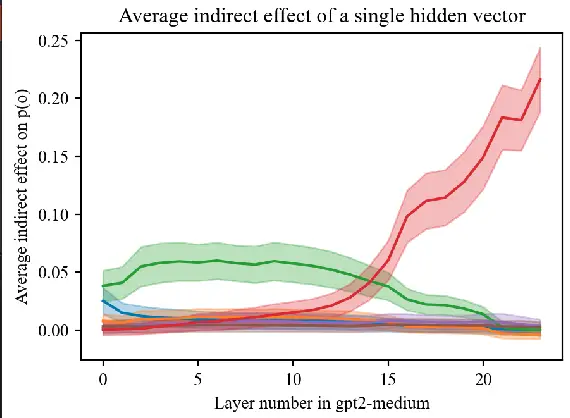

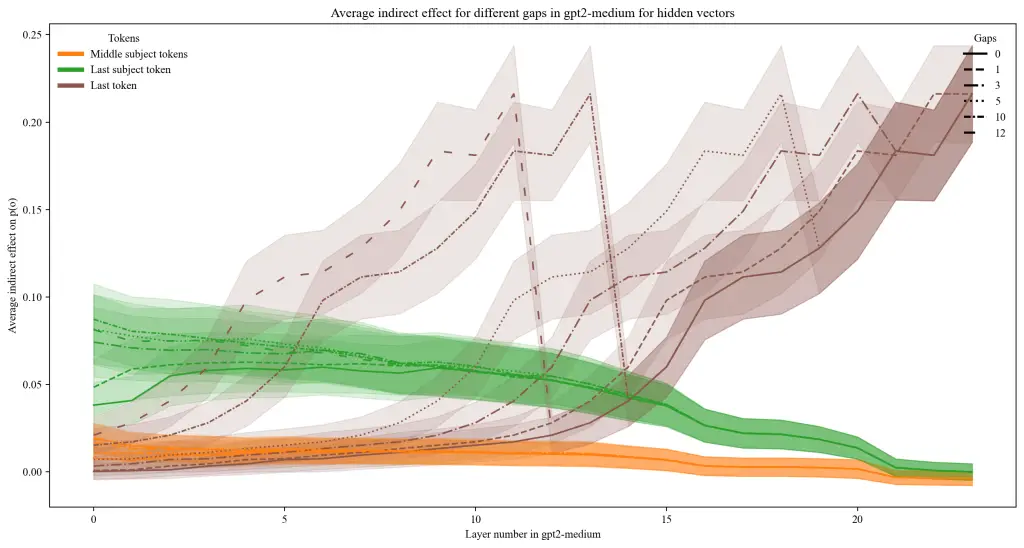

As part of the AI Safety Collab Germany 2024, I built a tool to investigate this question using a technique called causal tracing. It’s a bit like playing detective inside the AI: you mess with its input, and then trace which parts of its internal process are responsible for producing the correct answer. This helps pinpoint which layers or components are critical for factual knowledge.

What made my project unique—and helped it win the competition—was that I went beyond simply applying this method. I extended the method to trace how information flows across different layers and then analyzed whether there’s a consistent correlation between the activity of different layers when the model retrieves factual knowledge. This adds a new angle to understanding how knowledge is not just stored in one spot, but may be redundantly or cooperatively encoded across the model.

One of the core results is that while the final vector is the most crucial in restoring the information, the knowledge can be also substantially preserved when both restoring an early and a central layer. This points to new dynamics of information flow in LLMs which are yet to be studied. The notebook with all results is available online.

ML for MC integration

Almost all particle physics predictions are obtained by computing integrals like the cross section, many of which are calculated numerically using Monte Carlo methods. However, due to their complex structure this comes at an extremely high computational cost. Machine learning offers new ways to optimize the integration process, which significantly improves the success of methods like adaptive importance sampling beyond the capabilities of current approaches like VEGAS.

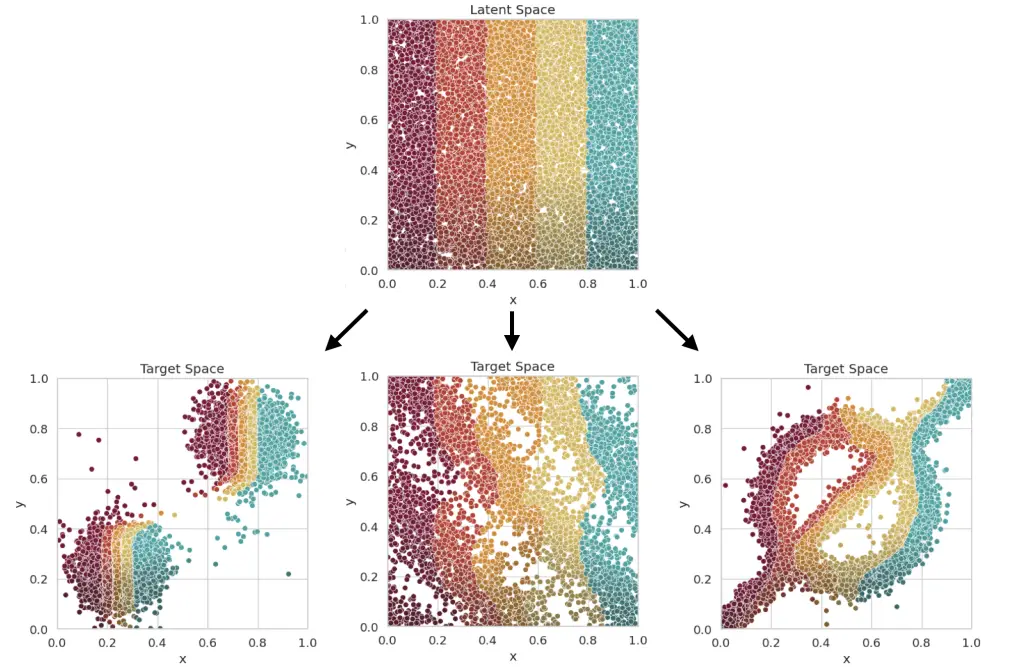

In my Master’s Thesis, I worked on Neural Importance Sampling. This method achieves a reduction of the variance of the integrator (and by this an improvement of the precision of the integral) by learning the optimal sampling of the latent variables. This is done by training a neural network which learns the optimal parameters of a normalizing flow. This normalizing flow transforms the originally uniformly distributed latent variables. The normalizing flows are realised using coupling cells, which contain the neural network which control the transformation. The mapping combination of multiple coupling cells determine the mapping, which is sketched in the lower right.

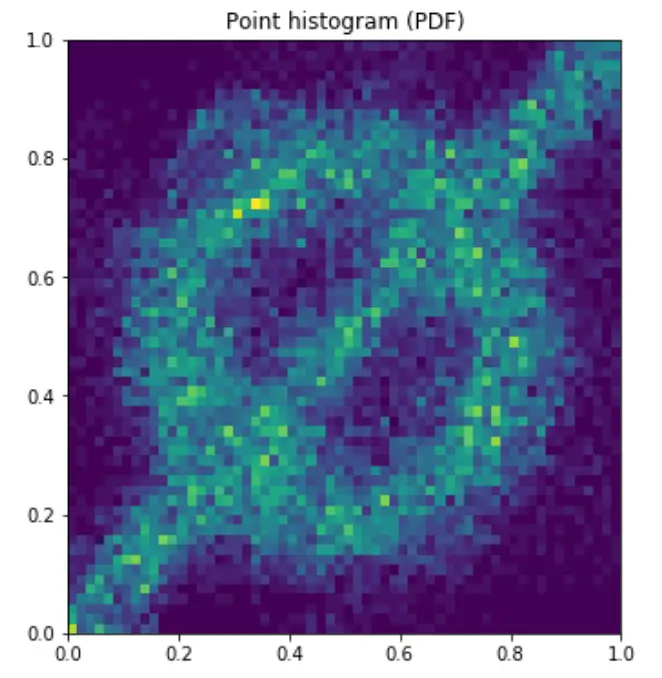

The advantage of this approach lies in the fact that it is adaptive and does not require any knowledge of the integrand. Together with a quasi-flat phase space generator, this allows fast integration also on a GPU architecture. Other than the very common adaptive approach VEGAS, this integration strategy does not fail for correlations along the integration axes. An example for this is the slashed circle function. The picture below shows how the Neural Importance Sampling learns different distributions. The VEGAS algorithm would not be able to learn this distribution efficiently as both axes are maximally correlated.

In my Master’s Thesis, I developed both multiple approaches of Neural Importance Sampling as well as a quasi-flat phase space generator. A demonstration of the strength of this approach is given in this demo jupyter notebook, which shows how to use the python package I developed.

I have continued my work on this promising approach by contributing to the ZüNIS package. A paper presenting the results with this novel method has been published in the reknown Journal of High Energy Physics.

Imprint & Privacy Notice © Niklas Götz, 2025